In an effort to provide a long-term solution to road congestion, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) initiated studies on three separate mass transit systems during the late 20th century.

The first of the schemes to open (one was wholly abandoned), the Bangkok Transit System (BTS), widely referred to as Skytrain, opened on 5 December 1999.

It seemed a turning point for the capital of Thailand in that rail-based public transport was belatedly being deployed as way of offsetting reliance on-road vehicles that were not progressing in terms of making the city function efficiently.

The densely populated city, approaching 10 million inhabitants at the time of the project’s start, was crippled by appalling road congestion that stifled business life and was causing some of the world’s worst air pollution.

A massive 82% of the city’s journeys during the early 1990s were by bus, car motorbike or taxi, and average vehicle speeds in the centre dropped to as low as 10km/h (6mph).

The project

The cost of building the first phase of the system was $1,800m, almost twice that of a comparable line in Manila, Philippines. Lending banks were promised 680,000 passenger journeys per day (a 16% rate of return), but early traffic figures of about 105,000 passengers per day were only just covering operating expenses.

The reason for the low ridership was partly the high cost of fares at up to three times the parallel bus service. Other basic problems, the brevity of the system and not covering main commuter arteries beyond the central district, did little to motivate would-be regular passengers.

Tender documents for a turnkey system were issued in March 1993 to five interested consortia, and in July the following year, the Siemens/Italian-Thai Development consortium signed up to build and operate the line. This agreement was later broadened to cover maintenance initially for five years, then extended to 2012.

Despite the system being laden with serious debts and lower-than-expected ridership, further extensions to the Skytrain network were announced in September 2006.

Infrastructure

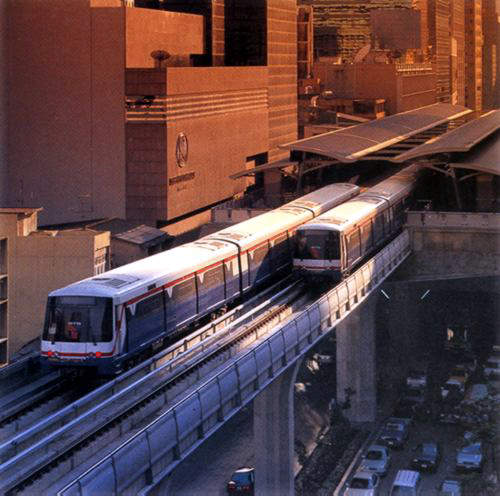

From contract signature to the operation of the first service trains took four-and-a-half years, a remarkably short time given the scale of the infrastructure works, and the busy nature of the city amidst which they worked. On opening, the system operated a minimum two-minute interval service.

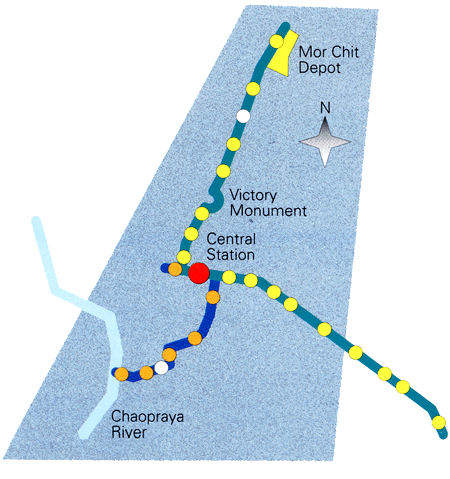

The system was handed over a month ahead of schedule. The network remains as built, comprising two lines totalling 23.1km. The Sukhumvit line is 16.8km-long, and runs from On Nut to the Mo Chit bus terminal. The Silom line runs 8.5km from the National Stadium to Sathorn Bridge on the banks of the Chaopraya River.

These lines intersect through the city centre, and both have an interchange at Central station, the main heavy rail terminus.

They were to gain interchanges at three points with Bangkok’s other modern rail mode, the single-line Metro (‘Blue Line’) that began revenue services in July 2004. The newer sub-surface operation is run independently of Skytrain by the Bangkok Metro Public Company Limited.

Trains run on dual tracks, fixed directly to concrete plinths, carried on a 9m-wide viaduct. The plinths are supported on single box viaduct girders, each 12m above the road level. The concrete foundations have been piled underground to a depth of 50m.

In 2004, the Commission for the Management of Land and Traffic granted THB46,704m to extend the mass transit network to 291km around the city, within six years. The expansion also includes three new lines at a total of 91km, Blue Line (27km), Orange Line, from Bang Kapi to Bang Bumru (24km) and Purple Line, from Bang Yai to Rat Burana (40km).

About 461,000 passengers per day are expected to use the service in 2010. It is estimated to reduce energy consumption costs by THB25,595m.

Work on the Skytrain extension will encompass moving trees, upgrading street isles, underground telephone lines, electric lines, pipes of underground telephone lines, strip electric line 69/115kV, strip electric line 24kV and sidewalk drain pipes.

In addition, the extension work involves rail structures, BTS station rail work and bogey operation system works.

Rolling stock

In total 35 new three-car trains were built for the system. Supplied by Siemens (who were also to be rolling stock contractors for Bangkok Metro), each train is 65.1m-long with a nominal capacity of just under 1,000 passengers. The three-car trains can be doubled in length at peak times.

Power comes from a third conductor rail, supplied at 750v DC.

Each car is air-conditioned and connected to adjoining cars by inter-car gangways. Regenerative braking is fitted.

The train sets and on-board equipment were tested in Europe before shipping, to ensure a smooth commissioning process. Each train is fitted with Siemens IGBT-3 three-phase traction control for optimum delivery of power to the driving wheels.

Signalling and communications

Unlike some other elevated light rail systems such as Vancouver Skytrain and London’s Docklands Light Railway, trains are manually driven.

Automatic train control systems allow units to take into account the status of the line ahead, with speeds adjusted to take into account prevailing conditions.

The engagement of a single consortium to build the infrastructure and rolling stock gave the ability to ensure maximum compatibility between the trains and other fixed equipment.

The future

Engineering work for extensions has taken place and expansion plans remain such as those to serve outer districts to stimulate trade by breaking out of the limited scope offered by the central zone.

However, the operation of the Bangkok Skytrain remained problematic and with financial concerns.